Daniel Schmid, the director, on his film.

Increasingly I think of myself as making forays across the faltering line between the actual and the dream, between reality and imagination. For as long as I can remember I’ve been following that narrow path, smuggling things back and forth from one side to the other.

The idea of making a film with old opera stars living long forgotten in a palace in Milan, appealed to my interest in this area wLere fiction and documentary meet.

I was well aware of the danger inherent in the theme, namely the combination of pathos with banality, the grotesqueness of it and the element of exposure tied up with tbat. Here again that faltering path.

These former singers all live out the stories of their lives in a fictitious setting, and none of them knows exactly anymore what is true and what actually happe- ned. They claim to be 80 years old and are in fact 90; their suitcases are ready in their rooms, packed for the journey, although they have lived here for ten or twenty years already. And the time since their last performance dwindles to a few years. When asked when they made their last recording, they reply: “Oh, at least three of four years ago” – but in fact perhaps 40 or 45 years have gone by. The boundary between reality and fantasy moves back and forth for them with the utmost ease, which appeals to me greatly as this constantly happens to me too. It makes for a kind of intermediate reality; for if one has imagined something for thirty years, it becomes onels reality whether it has happened or not. In addition these former singers are distinguished by the healthy portion of exhibitionism required in order to be able to perform. And finally, our work itself was an at- tempt to play with the boundary between documentary and fiction. But to clarify this, I must back-track a bit.

Because of the presence of the camera, every shot in a film is an act of terrorism and pornography. And the more seriously we wish to practice our profession – as a craft, because I regard myself as a craftsman not as an artist – the more we play the part of the vampire; meaning, one sucks out the strength of those out front, as an act of provocation. And this was certainly the case in Milan; only these peo- ple know what was going on from their stage experience. That gave us the possi- bility to count on them as accomplices right from the start and for us to treat each other playfully. A flourishing dependence does indeed exist between “vampires” and their “victims”

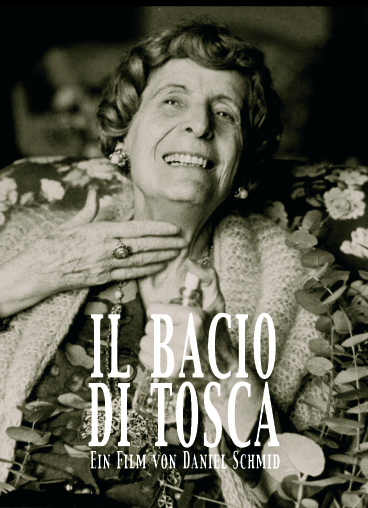

Certainly this has something to do with manipulation; but, firstly, this is the basis of all directorels work anyway and, secondly, in this case this existed within a conspiritorial relationship. One old singer still has his trunk from his transatlan- tic tour stored in the cellar. We heard of this and went down to the cellar together and shot the scene with the old operatic couple, trying on his costumes from pro- ductions of years ago. Or the incident with Sara Scuderi, who was one of the most brilliant interpretors of “Tosca” in the twenties and is 80 years old now: she was not going to sing, as her doctor had forbidden it. But when I struck up a Puccini motif on the piano, something inside her changed and for a second she became a primadonna again, with an audience of 3,000 in front of her. And for the end of the film, we built a stage next to a curtain in the Casa, ran taped applause from La Scala and staged last curtain calls. Everyone came out from behind the curtain and took a final bow. And behind the curtain all hell was let loose, walking sticks were thrown aside, age, aches, ailments were all forgotten as everyone pushed to the front – while knowing full well it was a fake situation.

Even if the gestures and airs of these former stars now tend to the grotesque, they also exude a dignity and greatness which is unique. The institution “Casa Verdi”, as a whole, is something wonderful; and it is to be found in what is for me the most marvellous, humane country in the world. If culture is that which is left over when everything has been forgotten, then it is continously present every- where in Italy. In the “Casa Verdi” the very chamber-maids are encyclopaedia of the opera: this staff would have enchanted Paeolini. No other land has anything like it. Only in Italy does this type of humane culture which is in no way “bour- geois” exist, infiltrating everything and sanctioning the existence of such a unique institution.

“La voce in bellezza”, it’s a question of a few years, perhaps ten; and then some- time or other the point is reached where it’s downhill from now on and a singer has to aak himself whether or not he should retire. The residents of the Casa Verdi all have this experience behind them, and now here they sit in their rooms – more protected than other old people, for the Casa has a doctor, three nurses, a physiotherapy unit and a staff of about twenty to care for the well-being of its pen- sioners. The external setting of their lives has been reduced to furnishings which are identical in all rooms, a few personal photographs, postcards and television, on which they occasionally watch an opera broadcast: nowhere in the world is such a critical opera audience to be found. Almost all performances fall below their standards and they are particularly hard on singers in their own respactive registers. In the mornings they sit in these little rooms, which have nothing in common with the Casa’s

magnificent reception rooms, busily preparing for their “entrance” at 11 o’clock in the corridor. Then they wander about the passages and wait for lunch in the vicinity of the dining-room, always an hour too early. For example, I once wit- nessed one such “entrance” in the telovision room, when a former star came in, heard the Eurovision tune and, joining in the music, swept through the empty television room singing – probably in the style of her entrances on stage at La Sca- la.

These entrances are a perpetual “make-believe”, always somewhat over the top. But I was impressed by the fact that each one was on his own “wavelength”, his own “channel”, that friendships hardly exist. On the other hand competition is rife, which apparently keeps them young: one wants to speak to so-and-so, the others claim he is dead. Then the door opens and in walks the supposedly dead man. In this respect they are utterly shameless. On one occasion I obviously spoke at too great length to one old opera star; anyway the next day her portrait of Puc- cini, personally dedicated to her by him, was scratched-all over. And when I asked who would come to a Gala Evening in La Scala, the reaction was the same every- where: “Who for? For Callas? No, I don’t think I’ll go”. Once again they refuse out of competitiveness, but also because they are convinced that La Scala, and opera in general, are ina decline, and because the opera in which they once sang touch them painfully.

The «Casa Verdi» in Milan

Giuseppe Verdi, who had no direct heirs, carried the idea of a «Casa di riposo», a retreat, around with him for ten years. Two years before his death the neo- renaissance building was completed. He had built it on the Piazza Buonarroti in Milan with the help of the architect Camille Boito, brother of Arrigo Boito, his librettist of many years’ standing. But he did not want the home to be opened be- fore his death, as he did not like being thankad. On the other hand he wanted to be buried in the Casa’s crypt, together with his second wife, Giuseppina Streppo- ni, who had been a famous primadonna in the 1840’s.

Verdi intended the home for musicians, in particular of course for the «gente del spettacolo lirico» – for those of the opera, who «were less fortunate in life than I and who were not endowed with the gift of thrift”. He laid down in his will that all his royalties were to go to the «Fondazione Giuseppe Verdi» and thus to the old people’s home. Since its opening on 10th October, 1902, the birthday of the composer who had died the previous year, more than 1,000 composers, conduc- tors, musicians and singers have found a home there. The regulations for admis- sion follow the hierarchy of the opera itself: first composers are offered a room, then conductors, and then down the ranks, ending with members of the chorus. Today the house accomodates around 65 people, mostly aged between 80-96 years, five of which are former stars of the thirties: first and foremost Sara Scuderi, then Irma Colasanti, Giuseppina Sani, Giulia Scaramelli and Ginseppe Manacchini.

In 1962 the rights on Verdi’s complete works expired; since thenthe Casa Verdi has been living off its capital. In 1978, in a very difficult financial situation, the «Associazione di amici della casa di riposo» was founded, which has raised more than 100 million lire over the last few years, partly from donations and partly from the personal support of singers. Thus for example Luciano Pavarotti gives a concert once or twice a year for the Casa Verdi.

What will happen in the future, however, is still uncertain.

Documentary-fiction,

Documentary-fiction, CH 1984, 87′, colour, Video/35mm

Director Daniel Schmid

Original version: Italian